In 1938, the visionary designer R. Buckminster Fuller wrote Nine Chains to the Moon, his radical proposal for improving the quality of life for all humankind via progressive design and maximization [1] of the world’s finite resources. The title was a metaphor for cooperation – if all of humankind stood on each other’s shoulders we could complete nine chains to the moon. Today, the population of the planet has increased more than three times to 6.7 billion (we could now complete 29 chains to the moon), and the successful distribution of energy, food, and shelter to over 9 billion humans by 2050 requires some fantastic schemes. Like Fuller’s revelation from five decades earlier, 29 Chains to the Moon features artists who put forth radical proposals, from seasteads and tree habitats to gift-based cultures, to make the world work for everyone.

Nostalgia for our alternate future is in the ether on this convergence of anniversaries: 2009 marks the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, the centennial of Futurism, and the quadricentennial of the Newtonian telescope. Over the last year, major art museums have presented exhibitions of visionary design and architecture [2] , meant to reignite that spark of collective imagination that the 20th century saw via world fairs [3] , the formation of international space agencies, and the promise of better living through technology.

Among the surveys was the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2008 exhibition, Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe. Viewers familiar with Fuller’s pragmatic geodesic domes and octet truss structures were introduced to his lesser-known concepts for tomorrow’s cities, like Dome over Manhattan (Midtown Manhattan acclimatized by a 2-mile diameter glass dome); Cloud Nine (a spherical cloud city that could levitate an entire community), and Triton City (a modular seastead for 100,000 inhabitants). Despite having a hallucinatory, science fiction veneer, these proposals were serious enough to be examined by agencies like the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development, which commissioned the study for Triton City, and, along with the U.S. Navy, approved the design.

If one of Fuller’s futuristic communities had been realized, it would not have been the first time that science fiction became science fact. In 1945, author, inventor and futurist Arthur C. Clarke predicted geostationary communications satellites, some 15 years ahead of NASA’s launch of Echo, the agency’s first experimental communications satellite project [4]. In 1941, Isaac Asimov popularized the term “robotics” in his short story, Liar, over three decades before Carnegie Mellon University founded The Robotics Institute in 1979. Aldous Huxley foresaw cloning decades before Dolly the sheep was made incarnate (again), and countless other authors and artists envisioned technological milestones – from the creation of the atomic bomb to nanotechnology – and their social implications in advance of their manifestation.

It’s not so easy to instill in the public the same brand of wonder and nationalist pride that the Space Race evoked from 1958 to 1975. One seismic shift of late has been the redirection of major scientific exploration from countries to private corporations and citizens [5]. Unbridled individual potential is one outcome of the information age, but so is ambient fear of the future. A 2002 Time Magazine poll revealed that 30 percent of its respondents believed that the world would end within their lifetimes. The work in this exhibition corresponds to the other 70 percent of the population that is optimistic despite the massive challenges faced by civilization [6]. These artists seize technologies that provide unprecedented platforms for collaboration, and new ways of visualizing and representing reality. Theirs is a moment of fluid exchanges between artistic and scientific disciplines, and cooperation among private and public institutions, toward the realization of a possible future.

– Andrea Grover, Curator, 29 Chains to the Moon

Footnotes

[1] Fuller called this ephemeralization, or doing more with less. It refers to the tendency for current technologies to be replaced by ones smaller, lighter, and more efficient.

[2] Design and the Elastic Mind was another important survey of anticipatory design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2008.

[3] The next registered “world exposition” will be Expo 2010 in Shanghai, China with the theme of “Better City, Better Life.”

[4] According to the Buckminster Fuller Institute, Fuller and Clarke were lifelong friends, who “shared a common fascination with the concept of a "space elevator" (the subject of Clarke's book The Fountains of Paradise) and Clarke wrote in his introduction to Buckminster Fuller: Anthology for a New Millennium, "when the space elevator is built, sometime in the twenty-first century, it will be his greatest memorial."

[5] Private corporations like Virgin Galactica and SpaceX are entering what was once exclusively the domain of government science agencies. Prizes like X Prize (which promotes “revolution through competition”), with initiatives in space travel, automotive design, and genomics, requires registered teams to be 90 percent privately funded.

[6] In September 2000, world leaders came together at United Nations Headquarters in New York to adopt the United Nations Millennium Declaration, committing their nations to a new global partnership to end poverty and hunger, provide universal education, gender equality, child and maternal healthcare, combat HIV/AIDS, and create environmental sustainability, via global partnership. With a deadline of 2015, these have become known as the Millennium Development Goals.

Open_Sailing is a multi-disciplinary international team led by Cesar Harada and Hiromi Ozaki that is revolutionizing the concept of seasteading and social production of ideas and technologies. The Open_Sailing prototype is a “living architecture” at sea, composed of multiple dwellings, ocean farming modules, and an amoeba-like design that can expand and contract, based on the existence of calculated risks. “Open_Sailing acts like a superorganism, a cluster of intelligent units that can react to their environment, change shape and reconfigure themselves. They talk to each other. They’re modular, re-pluggable, pre-broken, post-industrial.” The concept for Open_Sailing came from creating a geography of fear – a world “potential threat map” that highlighted the centers of greatest risk (pandemics, high-human density, recent violent conflicts, hypothetical nuclear fall-outs, tsunami risk, potential exposure to rising sea level, and so on), to determine the safest areas on Earth, which happened to be at sea. Open_Sailing was awarded the 2009 Prix Ars Electronica in “THE NEXT IDEA” category, and is underway with construction of an advanced prototype for their floating laboratory. www.opensailing.net

Open_Sailing is a multi-disciplinary international team led by Cesar Harada and Hiromi Ozaki that is revolutionizing the concept of seasteading and social production of ideas and technologies. The Open_Sailing prototype is a “living architecture” at sea, composed of multiple dwellings, ocean farming modules, and an amoeba-like design that can expand and contract, based on the existence of calculated risks. “Open_Sailing acts like a superorganism, a cluster of intelligent units that can react to their environment, change shape and reconfigure themselves. They talk to each other. They’re modular, re-pluggable, pre-broken, post-industrial.” The concept for Open_Sailing came from creating a geography of fear – a world “potential threat map” that highlighted the centers of greatest risk (pandemics, high-human density, recent violent conflicts, hypothetical nuclear fall-outs, tsunami risk, potential exposure to rising sea level, and so on), to determine the safest areas on Earth, which happened to be at sea. Open_Sailing was awarded the 2009 Prix Ars Electronica in “THE NEXT IDEA” category, and is underway with construction of an advanced prototype for their floating laboratory. www.opensailing.net

Stephanie Smith’s projects span the worlds of architecture, art, technology, and culture. Her research into the social practices of fringe and nomadic societies yielded a movement she calls Wanna Start a Commune?, and include diagrams for creating modern Cul-de-Sac Communes, portable kiosks for non-monetary exchange and meet-ups, and most recently an online platform for creating as many communes as your life demands, (www.wecommune.com). Smith says that the impetus for these projects was to counter the assumption that being green means consuming green products; instead she wanted to revive the best parts of the commune concept (a community where resources are shared) and “bring collective attitude to places where it doesn't yet exist.” Smith is also the founder of Ecoshack, a design experiment that began in Joshua Tree, CA and is now an LA-based design studio inspired by the ad hoc, indigenous and archetypal typologies typically found at the fringes of society and culture. In 2008, the Whitney Museum identified Smith as the designer/entrepreneur most actively taking the ideas of Buckminster Fuller into the 21st century.

Stephanie Smith’s projects span the worlds of architecture, art, technology, and culture. Her research into the social practices of fringe and nomadic societies yielded a movement she calls Wanna Start a Commune?, and include diagrams for creating modern Cul-de-Sac Communes, portable kiosks for non-monetary exchange and meet-ups, and most recently an online platform for creating as many communes as your life demands, (www.wecommune.com). Smith says that the impetus for these projects was to counter the assumption that being green means consuming green products; instead she wanted to revive the best parts of the commune concept (a community where resources are shared) and “bring collective attitude to places where it doesn't yet exist.” Smith is also the founder of Ecoshack, a design experiment that began in Joshua Tree, CA and is now an LA-based design studio inspired by the ad hoc, indigenous and archetypal typologies typically found at the fringes of society and culture. In 2008, the Whitney Museum identified Smith as the designer/entrepreneur most actively taking the ideas of Buckminster Fuller into the 21st century.

Mitchell Joachim [jo-ak-um] is a Co-Founder at Terreform ONE and Terrefuge. He earned a Ph.D. at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MAUD at Harvard University, M.Arch. at Columbia University, and BPS at SUNY Buffalo with Honors. He currently serves on the faculty at Columbia University and Parsons and formerly worked as an architect at Gehry Partners and Pei Cobb Freed. He has been awarded the Moshe Safdie Research Fellowship and the Martin Family Society Fellow for Sustainability at MIT. He won the History Channel and Infiniti Design Excellence Award for the City of the Future and Time Magazine’s “Best Invention of the Year 2007” for Compacted Car with MIT Smart Cities. His project on view at the Miller Gallery, Fab Tree Hab, has been exhibited at MoMA and widely published. He was selected by Wired magazine for "The 2008 Smart List: 15 People the Next President Should Listen To." www.archinode.com

Terreform ONE is a non-profit philanthropic design collaborative that integrates ecological principles in the urban environment. The group views ecology in design as not only a philosophy that inspires visions of sustainability and social justice but also a focused scientific endeavor. The mission is to ascertain the consequences of fitting a project within our natural world setting. Solutions range from green master planning, urban self-sufficiency infrastructures, community development activities, climatic tall buildings, performative material technologies, and smart mobility vehicles for cities. These design iterations seek an activated ecology both as a progressive symbol and an evolved artifact.

Terreform ONE is a non-profit philanthropic design collaborative that integrates ecological principles in the urban environment. The group views ecology in design as not only a philosophy that inspires visions of sustainability and social justice but also a focused scientific endeavor. The mission is to ascertain the consequences of fitting a project within our natural world setting. Solutions range from green master planning, urban self-sufficiency infrastructures, community development activities, climatic tall buildings, performative material technologies, and smart mobility vehicles for cities. These design iterations seek an activated ecology both as a progressive symbol and an evolved artifact.

SPECIAL READING ROOM WITH MATERIALS FEATURING

The Buckminster Fuller Institute

Lowry Burgess, Space Artist and CMU Professor

International Space University

The Seasteading Institute

~~~~~~

Andrea Grover is an independent curator, artist and writer. In 1998, she founded Aurora Picture Show, a now recognized center for filmic art that began in her living room as “the world’s most public home theater.” She curated the first exhibition exploring the phenomenon of crowdsourcing in art (Phantom Captain, apexart, New York, 2006), and, with artist Jon Rubin, organized an exhibit in which worldwide participants created a photo-sharing album of their imaginings on Tehran (Never Been to Tehran, Parkinggallery, Tehran, Iran, 2008) She recently curated screenings for both Dia Art Foundation, New York, and The Menil Collection, Houston. 29 Chains to the Moon continues her research into cooperation and distributed thinking across disciplines.

Images, top to bottom:

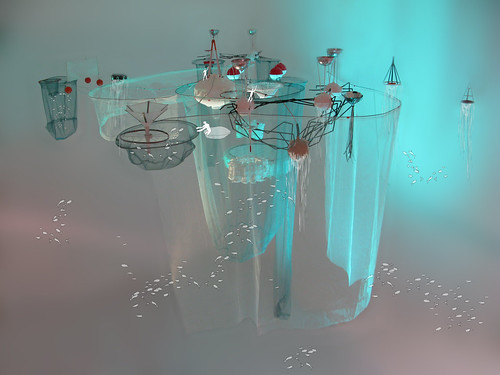

Open_Sailing Model, Open_Sailing (model made by Martin Gautron, Hiromi Ozaki, Adrien Lecuru, and Cesar Harada)

The Cul-de-sac Commune Project, Stephanie Smith

Fab Tree Hab, Terreform ONE, (contributors: Mitchell Joachim, Maria Aiolova, Landon Young, Javier Arbona, Lara Greden)

4 comments:

All this alt-future optimism makes me think of Kim Stanley Robinson's incredible Mars Trilogy, easily the last, great optimistic masterpiece of science fiction. A collective future? Yes please.

I love this show (sadly from afar). Thanks for posting your essay.

Alex, I am going to track down Mars Trilogy. Thanks for the suggestion. I also recommend a non-fiction book by Marshall Savage: The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps. My copy is on loan to the exhibition. I am *optimistic* we will meet in the future.

thank you, this website has provided very useful knowledge cara cepat memperbesar penis for me and others

Nice info. Thank you.

all face the modern home design problem. finish with a specifications price honda cbr calm heart and interior home design brain are cold and are trying so hard ...

Post a Comment